Apue Ipc 1 进程间通信

Interprocess communication

###Pipe

Two Limitations

- half-duplex

- used only between processes that have a common ancestor

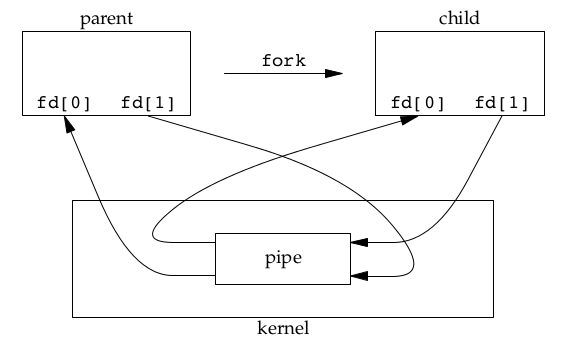

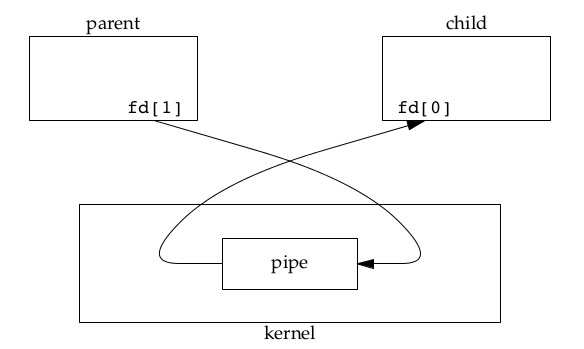

Normally, a pipe is created by a process, that process calls fork, and the pipe is used between the parent and the child.

Every time you type a sequence of commands in a pipeline for the shell to execute, the shell creates a separate process for each command and links the standard output of one process to the standard input of the next using a pipe.

#include <unistd.h>

int pipe(int fd[2]);

A pipe in a single process is next to useless. Normally, the process that calls pipe then calls fork, creating an IPC channel from the parent to the child, or vice versa.

When one end of a pipe is closed, two rules apply:

-

If we read from a pipe whose write end has been closed, read returns 0 to indicate an end of file after all the data has been read.

-

If we write to a pipe whose read end has been closed, the signal SIGPIPE is generated. If we either ignore the signal or catch it and return from the signal handler, write returns −1 with errno set to EPIPE.

When we’re writing to a pipe (or FIFO), the constant PIPE_BUF specifies the kernel’s pipe buffer size. A write of PIPE_BUF bytes or less will not be interleaved with the writes from other processes to the same pipe (or FIFO). But if multiple processes are writing to a pipe (or FIFO), and if we write more than PIPE_BUF bytes, the data might be interleaved with the data from the other writers. We can determine the value of PIPE_BUF by using pathconf or fpathconf (recall Figure 2.12).

####Popen

#include <stdio.h>

FILE *popen(const char *cmdstring, const char *type);

Returns: file pointer if OK, NULL on error

int pclose(FILE *fp);

Returns: termination status of cmdstring, or −1 on error

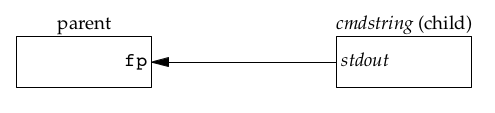

what popen does is creating a pipe, forking a child, closing the unused ends of the pipe, executing a shell to run the command, and waiting for the command to terminate.

The function popen does a fork and exec to execute the cmdstring and returns a standard I/O file pointer. If type is “r”, the file pointer is connected to the standard output of cmdstring. If type is “w”, the file pointer is connected to the standard input of cmdstring,

If the shell cannot be executed, the termination status returned by pclose is as if the shell had executed exit(127)

Note that popen should never be called by a set-user-ID or set-group-ID program. When it executes the command, popen does the equivalent of

execl("/bin/sh", "sh", "-c", command, NULL);

One thing that popen is especially well suited for is executing simple filters to transform the input or output of the running command. Such is the case when a command wants to build its own pipeline

###FIFO

the relation between PIPE and FIFO :

- PIPE are unnamed pipes, can only be used between relate process when common ancestor has created them

- FIFOs are sometimes called named pipes. however unrelated processes can exchange data

- PIPE can be used only for linear connections between processes

- FIFO has a name, so it can be used for nonlinear connections.

- FIFO can be used to duplicate an output stream in a series of shell commands.

- PIPE IPC structure completely removed when the last process to reference it terminates.

- FIFO the name of IPC structure stays in the file system until explicitly removed, any data left in a FIFO is removed when the last process to reference the FIFO terminates.

-

FIFO prevents writing the data to an intermediate disk file, as well PIPE

#include <sys/stat.h> int mkfifo(const char *path, mode_t mode); int mkfifoat(int fd, const char *path, mode_t mode); Both return: 0 if OK, −1 on error

When we open a FIFO, the nonblocking flag (O_NONBLOCK) affects what happens.

-

In the normal case (without O_NONBLOCK), an open for read-only blocks until some other process opens the FIFO for writing. Similarly, an open for write only blocks until some other process opens the FIFO for reading.

-

If O_NONBLOCK is specified, an open for read-only returns immediately. But an open for write-only returns −1 with errno set to ENXIO if no process has the FIFO open for reading.

As with a pipe, if we write to a FIFO that no process has open for reading, the signal SIGPIPE is generated. When the last writer for a FIFO closes the FIFO, an end of file is generated for the reader of the FIFO.

It is common to have multiple writers for a given FIFO. This means that we have to worry about atomic writes if we don’t want the writes from multiple processes to be interleaved. As with pipes, the constant PIPE_BUF specifies the maximum amount of data that can be written atomically to a FIFO.

There are two uses for FIFOs:

-

FIFOs are used by shell commands to pass data from one shell pipeline to another without creating intermediate temporary files.

-

FIFOs are used as rendezvous(交汇的) points in client–server applications to pass data between the clients and the servers.

mkfifo fifo1

prog3 < fifo1 &

prog1 < infile | tee fifo1 | prog2

###XSI IPC

####identifiers and key

Each IPC structure (message queue, semaphore, or shared memory segment) in the kernel is referred to by a non-negative integer identifier. To send a message to or fetch a message from a message queue, for example, all we need know is the identifier for the queue. Unlike file descriptors, IPC identifiers are not small integers. Indeed, when a given IPC structure is created and then removed, the identifier associated with that structure continually increases until it reaches the maximum positive value for an integer, and then wraps around to 0.

The identifier is an internal name for an IPC object. Cooperating processes need an external naming scheme to be able to rendezvous using the same IPC object. For this purpose, an IPC object is associated with a key that acts as an external name

Whenever an IPC structure is being created (by calling msgget, semget, or shmget), a key must be specified. The data type of this key is the primitive system data type key_t, which is often defined as a long integer in the header < sys/types.h>. This key is converted into an identifier by the kernel.

There are various ways for a client and a server to rendezvous at the same IPC structure:

- The server can create a new IPC structure by specifying a key of IPC_PRIVATE and store the returned identifier somewhere (such as a file) for the client to obtain. The key IPC_PRIVATE guarantees that the server creates a new IPC structure. The disadvantage of this technique is that file system operations are required for the server to write the integer identifier to a file, and then for the clients to retrieve this identifier later.

The IPC_PRIVATE key is also used in a parent–child relationship. The parent creates a new IPC structure specifying IPC_PRIVATE, and the resulting identifier is then available to the child after the fork. The child can pass the identifier to a new program as an argument to one of the exec functions.

-

The client and the server can agree on a key by defining the key in a common header, for example. The server then creates a new IPC structure specifying this key. The problem with this approach is that it’s possible for the key to already be associated with an IPC structure, in which case the get function (msgget, semget, or shmget) returns an error. The server must handle this error, deleting the existing IPC structure, and try to create it again.

-

The client and the server can agree on a pathname and project ID (the project ID is a character value between 0 and 255) and call the function ftok to convert these two values into a key. This key is then used in step 2. The only service provided by ftok is a way of generating a key from a pathname and project ID.

#include <sys/ipc.h> key_t ftok(const char *path, int id);

The path argument must refer to an existing file. Only the lower 8 bits of id are used when generating the key.

The key created by ftok is usually formed by taking parts of the st_dev and st_ino fields in the stat structure (Section 4.2) corresponding to the given pathname and combining them with the project ID. If two pathnames refer to two different files,then ftok usually returns two different keys for the two pathnames. However, because both i-node numbers and keys are often stored in long integers, information loss can occur when creating a key. This means that two different pathnames to different files can generate the same key if the same project ID is used.

The three get functions (msgget, semget, and shmget) all have two similar arguments: a key and an integer flag. A new IPC structure is created (normally by a server) if either key is IPC_PRIVATE or key is not currently associated with an IPC structure of the particular type and the IPC_CREAT bit of flag is specified. To reference an existing queue (normally done by a client), key must equal the key that was specified when the queue was created, and IPC_CREAT must not be specified.

Note that it’s never possible to specify IPC_PRIVATE to reference an existing queue, since this special key value always creates a new queue. To reference an existing queue that was created with a key of IPC_PRIVATE, we must know the associated identifier and then use that identifier in the other IPC calls (such as msgsnd and msgrcv), bypassing the get function.

If we want to create a new IPC structure, making sure that we don’t reference an existing one with the same identifier, we must specify a flag with both the IPC_CREAT and IPC_EXCL bits set. Doing this causes an error return of EEXIST if the IPC structure already exists. (This is similar to an open that specifies the O_CREAT and O_EXCL,flags.)

####Disadvantage

-

IPC structures are systemwide and do not have a reference count. They remain in the system until specifically read or deleted by some process calling msgrcv or msgctl, by someone executing the ipcrm(1) command, or by the system being rebooted.

-

IPC structures are not known by names in the file system We can’t see the IPC objects with an ls command, we can’t remove them with the rm command, and we can’t change their permissions with the chmod command. Instead, two new commands —ipcs(1) and ipcrm(1)—were added.

-

these forms of IPC don’t use file descriptors, we can’t use the multiplexed I/O functions (select and poll) with them.

####Advantage

- Flow control : sender is put to sleep if there is a shortage of system resources (buffers) or if the receiver can’t accept any more messages.

- Reliable : because of in single host

- Records

- Message type or priorities

####Message Queue

A message queue is a linked list of messages stored within the kernel and identified by a message queue identifier.

#include <sys/msg.h>

int msgget(key_t key, int flag);

Returns: message queue ID if OK, −1 on error

int msgctl(int msqid, int cmd, struct msqid_ds *buf );

int msgsnd(int msqid, const void *ptr, size_t nbytes, int flag);

Returns: 0 if OK, −1 on error

ssize_t msgrcv(int msqid, void *ptr, size_t nbytes, long type, int flag);

Returns: size of data portion of message if OK, −1 on error

Since a reference count is not maintained with each message queue (as there is for open files), the removal of a queue simply generates errors on the next queue operation by processes still using the queue. Semaphores handle this removal in the same fashion. In contrast, when a file is removed, the file’s contents are not deleted until the last open descriptor for the file is closed.

we shouldn’t use them for new applications.

###Semaphores

A semaphore is a counter used to provide access to a shared data object for multiple processes.

#include <sys/sem.h>

int semget(key_t key, int nsems, int flag);

Returns: semaphore ID if OK, −1 on error

int semctl(int semid, int semnum, int cmd, ... /* union semun arg */ );

int semop(int semid, struct sembuf semoparray[], size_t nops);

Returns: 0 if OK, −1 on error

sharing a single resource among multiple processes:

- semaphore : set SEM_UNDO gurant the process terminates, locking is released

- record locking : if process is terminates, kernel automatically release the lock

-

mutex : if process is terminates, recovery is difficult

Operation User(s) System(s) Clock(s) semaphores with undo 0.50 6.08 7.55 advisory record locking 0.51 9.06 4.38 mutex in shared memory 0.21 0.40 0.25

In each case, the resource was allocated and then released 1,000,000 times,This was done simultaneously by three different processes.

Why prefer record locking to mutex(unless preform is primary concern)?

- First, recovery from process termination is more difficult using a mutex in memory shared among multiple processes.

- Second, the process-shared mutex attribute isn’t universally supported yet.

###Share Memory

Shared memory allows two or more processes to share a given region of memory. This is the fastest form of IPC, because the data does not need to be copied between the client and the server.

#include <sys/shm.h>

int shmget(key_t key, size_t size, int flag);

Returns: shared memory ID if OK, −1 on error

If a new segment is being created (typically by the server), we must specify its size. If we are referencing an existing segment (a client), we can specify size as 0. When a new segment is created, the contents of the segment are initialized with zeros.

int shmctl(int shmid, int cmd, struct shmid_ds *buf );

Returns: 0 if OK, −1 on error

void *shmat(int shmid, const void *addr, int flag);

Returns: pointer to shared memory segment if OK, −1 on error

SHMLBA stands for "low boundary address multiple"

int shmdt(const void *addr);

Returns: 0 if OK, −1 on error

###POSIX Semaphores

Compare to XSI Semaphores

- The POSIX semaphore interfaces allow for higher-performance implementations

- The POSIX semaphore interfaces are simpler to use

- The POSIX semaphores behave more gracefully when removed

Two Flavors

-

unamed it exists in memory only and require that processes have access to the memory to be able to use the semaphores. it can be used only by threads in the same process or threads in different processes that have mapped the same memory extent into their address spaces.

#include <semaphore.h> int sem_init(sem_t *sem, int pshared, unsigned int value); int sem_destroy(sem_t *sem); int sem_getvalue(sem_t *restrict sem, int *restrict valp); Returns: 0 if OK, −1 on error

sem_getvalue Be aware, however, that the value of the semaphore can change by the time that we try to use the value we just read. Unless we use additional synchronization mechanisms to avoid this race, the sem_getvalue function is useful only for debugging.

-

named it is accessed by name and can be used by threads in any processes that know their names.

#include <semaphore.h> sem_t *sem_open(const char *name, int oflag, ... /* mode_t mode, unsigned int value */ ); Returns: Pointer to semaphore if OK, SEM_FAILED on error int sem_close(sem_t *sem) int sem_unlink(const char *name); int sem_trywait(sem_t *sem); int sem_wait(sem_t *sem); #include <time.h> int sem_timedwait(sem_t *restrict sem,const struct timespec *restrict tsptr); int sem_post(sem_t *sem); all return: 0 if OK, −1 on error

the performance of Linux POSIX semaphore outperform XSI semaphore,because of POSIX semaphores maps the file into the process address space and performs individual semaphore operations without using system calls.

###Summary After comparing the timing of message queues versus full-duplex pipes, and semaphores versus record locking, we can make the following recommendations: learn pipes and FIFOs, since these two basic techniques can still be used effectively in numerous applications. Avoid using message queues and semaphores in any new applications. Full-duplex pipes and record locking should be considered instead, as they are far simpler. Shared memory still has its use, although the same functionality can be provided through the use of the mmap function (Section 14.8).